Blog

Search the blog:

Oakes Smith, "The Willows," and General Washington

Plans for archeological excavation at Lakeview Cemetery in Patchogue, Long Island are underway. Specifically, experts will be examining the site of “The Willows,” home of Elizabeth Oakes Smith and Seba Smith from 1859 to 1870. The lives and work of both these writers are significant parts of literary and social history in the area…

Elizabeth Oakes Smith, “The Willows,” and General Washington

Timothy H. Scherman

Plans for archeological excavation at Lakeview Cemetery in Patchogue, Long Island are underway. Specifically, experts will be examining the site of “The Willows,” home of Elizabeth Oakes Smith and Seba Smith from 1859 to 1870. The lives and work of both these writers are significant parts of literary and social history in the area, but more significant, to many, is the possibility that the building purchased by the couple in 1859 was once the tavern where General Washington was entertained or housed on his tour of Long Island in 1790.

Diligent searches for legal records documenting the sequential sale and/or transfer of this property from the late 18thcentury to the date of the Smith purchase have been hampered by lapses in legal records, but the interest of Oakes Smith and her husband in the history of the US, the evidence of their significant investment in the storied life of Washington specifically, coupled with their financial means in 1859, argue strongly that their choice of a new home on Long Island was not random. Most important to recall is that while our records of the property’s provenance are incomplete now, 230 years after Washington’s visit, in 1859, only 70 years after the fact, the sequence of property ownership was doubtless much more clear. Proud of her financial success and continually interested, as a woman writer, in claiming the same rights as men to the documentation of American history, it would be completely fitting that, hearing of the Woodhull mansion’s relation to Washington’s stay, Elizabeth Oakes Smith would have made a special effort to purchase a property with such a link to American history.

Like most white Americans of the antebellum period, and particularly as writers and editors in the publishing industry in the 1830s and 40s, Elizabeth Oakes Smith and her husband read and wrote frequently of Washington as the “father of our country,” a modern mythic figure around which the ideals of the US population were centered. In the summer of 1847, however, Oakes Smith’s relation to Washington became more material and personal, when she visited the family of Judge Hagerman and the Hopper family near what is now Mahwah, New Jersey. There, she dined with an elderly member of the Hopper family who displayed part of a dinner service used to entertain Washington, and she enjoyed a tour of the area, where Judge Pierson, a key land owner in the area, pointed out to her the hemlock that marked the place where Washington camped during the Revolutionary war.

This experience made such an impression upon her that she began to incorporate this local history into several of her works—whether in prefatory remarks (as in her novel, The Salamander (1848), set in the Ramapaugh Valley of an earlier time) or in the main plot (her novel The Ramapo Pass: A Romance of the Revolution, (1848), in which Washington is a principal figure. In fact, Oakes Smith expanded the latter novel with a new more detailed preface remembering her visit with the Hoppers in a serial reprint, The Intercepted Messenger of Ramapo Pass in Emerson’s United States Magazine in 1856, a journal she edited along with her husband from 1856 to 1858, and then expanded the same work again for a novel in Beadle’s Dime Novel series under the title The Bald Eagle in 1867.

Most important, to her, was the authority such “local history” might provide for her as one documenting American history. In an 1849 letter to Benson Lossing, author of The Pictorial Fieldbook of the Revolution (1850), she shared the details of her visit to the Ramapaugh Valley, concluding, “I have been thus explicit, Sir, in giving you these details, because I consider them essential to this part of our history, and as throwing additional light upon the character of Washington.” When her anecdotes were incorporated in Lossing’s work, she proudly remarked in a letter dated March 1, 1851 “I am much gratified at being given an authority in your work, for I am very unwilling to be regarded as a mere Magazine writer, a compounder of mawkish stories, and sentimental poetry.”

Elizabeth Oakes Smith’s lecture career and her turn to the feminist cause from 1850 to 1857 turned her focus away from American history as such, but when she joined her husband as co-editor of Emerson’s United States Magazine (later The Great Republic Monthly) from 1856 through 1859, she returned to her work on Washington. The magazine’s series on “The Capitol at Washington,” followed by fourteen long installments of a serialized “Life of Washington” from June 1857 to November 1858 show a continued dedication to this central figure in US history.

In sum, especially given their immediately preceding work on Washington, lasting at least from 1847 to 1859, it would make perfect sense that Oakes Smith and her husband might choose to purchase the home in Patchogue that local residents knew, better than any lawyer, held a direct relation to one of the figures at the center of their work and American history. There were obviously current residents in Patchogue in 1859 who were living at the time of Washington’s visit, who needed no research archive or legal records to document the connection.

Oakes Smith on the Elitism of White Feminism

Even into my fourth decade recovering the work of Elizabeth Oakes Smith, her paradox continues to assert itself: how could such a ubiquitous and popular and to some notorious writer of the nineteenth century have been so firmly forgotten in our cultural history?

Even into my fourth decade recovering the work of Elizabeth Oakes Smith, her paradox continues to assert itself: how could such a ubiquitous and popular and to some notorious writer of the nineteenth century have been so firmly forgotten in our cultural history?

In 1978, the very powerful and respectable feminist historian Nina Baym declared Oakes Smith “not a team player” and her essentialist claim for women’s spiritual superiority a political dead-end. I suppose there is something to those claims, and why would scholars of the 2nd wave bother trying to refute them? Baym was a leader in the field, and there were/are all sorts of nineteenth century figures who did not write so much we need to sift through, whose style is more straightforward, whose positions are more clearly cut.

In the writing of anyone who writes as much as Oakes Smith did one is bound to find contradictions, and as I’ve argued, so often was she writing to accommodate--and manipulate—the expectations of paying readers and editors, it does take time to discern what her personal political positions really were. Moreover, those positions developed over time. But even before Oakes Smith joined the woman’s movement and participated in national conventions, her positions had become more progressive than has been acknowledged.

Reading over Woman and Her Needs for the umpteenth time as I proof volume II of her Selected Writings, I was struck by the end of a paragraph in the 10th chapter that I’ve never quoted before—perhaps never quite seen before. Not only does it answer the “team player” question—it responds directly to charges of white feminism’s elitism and exclusion of the voices of women not privileged to have their voices heard in the first wave. While neither Oakes Smith nor first wave white feminism succeeded to the extent we might have hoped, this sort of passage should inspire us to keep reading—and re-reading—texts that at first don’t seem to supply what we need.

Perhaps Oakes Smith was finally not a “team player,” but as I’ve argued elsewhere, much of the reason for that is that she could not afford it. That said, I’m not sure I’ve ever seen white feminist elitism called out by any white feminist in the 1850s as well as it is here:

Beauty and genius are easily emancipated, and hence we find in all ages beautiful and gifted women casting a halo over the dark features of an age, and misleading us into the belief that others were equally free; and these, affluent in homage, intoxicated in adulation, have unconsciously helped to deaden the cry of the many—the bitter cry of the ignorant and the oppressed, whose glory was turned to shame, and whose light had become darkness. It is cruel selfishness to fold our hands in idle contempt for the needs of others, because the Good Father has cast our lines in pleasant places.

Woman and Her Needs, 1851

Getting to Know Nancy

The first volume of Elizabeth Oakes Smith: Selected Writings (2023) considers Oakes Smith’s emergence as a public figure and her rise to fame, first in New York, and soon as a name widely recognized in the national media. The volume ends, however, with a countertext…

The first volume of Elizabeth Oakes Smith: Selected Writings (2023) considers Oakes Smith’s emergence as a public figure and her rise to fame, first in New York, and soon as a name widely recognized in the national media. The volume ends, however, with a countertext—Oakes Smith’s narrative account of her journey back to the middle of Maine, where she and her childhood friend Nancy Mosman became the first two white women to summit Mt. Katahdin. The trip for Oakes Smith was not only a break from the demands of editors and publishers cashing in on her name—it also seems to mark Oakes Smith’s decision to concentrate her energies on something more fulfilling and significant, though her correspondence admits she did not know just what that would entail.

It’s very important to remember that Oakes Smith was not the only woman on this excursion. Who, finally, was Oakes Smith’s woman partner on the journey, Nancy Crockett Mosman? In two fairly recent essays, “The Mount Katahdin Peaks: the First Twelve Women Climbers, 1849-1855 (2016) and The First Women on Katahdin: Was It a Race or Merely an Exciting Phase? (2018) William Geller documents the stories of Oakes Smith, Mosman, and ten other women who made the climb up Maine’s highest peak. In both essays, he mentions how little we know about most of these women (some seem to be treated by men like Keep as exotic baggage to carry), but he does supply more information about Mosman than anyone has to date:

Since 1989 Mosman’s name has appeared in two articles, with no other information about her. Nancy Crockett Mosman, born in 1822 and 16 years younger than Elizabeth Oakes Smith, grew up in Portland, Maine. In 1842 she married David Mosman, a successful Bangor hardware merchant, and they resided in Bangor. They raised two children, Mary and Fitz Howard, both born in Bangor before the ascent. Nancy was a supporter of and a contributor to the Female Medical Education Society and the New England Female Medical College in 1853. How Mosman and Smith knew each other remains unknown, but they both lived in Portland until 1838, and their families may have attended the same church. (Geller, 2018, 1)

We need to pursue Geller’s questions if we can, and already I think he’s concluded correctly that Mosman’s future as a female physician allows us to make some better sense of her relationship to Oakes Smith beyond their mutual origin in Portland. Higher education and the medical profession were goals of some of the most radical women of the day, and her pursuit of these may indicate the journey was in fact as much a political statement as it was a vacation of sorts.

But it’s quite a different thing to postulate abstractly about this journey than it is to put oneself in these women’s shoes and see what it actually entailed. Stan Tag is the only writer about this moment (that I know of) who has summited Katahdin via the Keep Path, but unfortunately, though he mentions the Oakes Smith/Mosman excursion, he focuses (like Geller) more on their writing of a (pretty sassy) note to Marcus Keep, original blazer of that trail, than he does on the physical experience. (see his “Forest Life and Forest Trees: Thoreau and John S. Springer in the Maine Woods”)

Cuz women were writers, right?

Maybe. In this instance, maybe not. True, Oakes Smith wrote about this experience, it seems, automatically; she turned everything she could into fodder for what would support herself and her family. But this was also her trip moving away from writing—at least of the kind she’d been doing, and maybe, in her mind—away from writing at all. Perhaps she envied her young friend Nancy, and the way her work had more tangible and immediate results than the cash one could make from writing.

* * *

When I traveled to Katahdin this past summer (2022), I had been to the mountain several times already, and I had traced Oakes Smith’s path with veteran guide Susan Adams from Hunt’s Farm, (more or less where any road into the region ends) through the woods, to Katahdin Lake. On another day, we traipsed the three easy miles from the lake to Avalanche Brook, where Keep decided it would be easier for those making the summit to get into the water, where they wouldn’t have to struggle through thick underbrush. I left the rest of the journey—those three more miles up the rocky stream, to the scree scramble up the Avalanche that tore off the side of the mountain in the 1820s, to Pamola peak—yeah, I left all that for another time. Sure, there had been a lot of misquitoes (how folks without DEET survived them I don’t know), but the hiking I’d done to that point?—well it was walking.

That is, what I had done so far wasn’t much of an adventure. In fact it was as close to an adventure “in the abstract” as it could be—something women of the nineteenth century might write about, as if it were more, I had to think. While Oakes Smith’s detailed narrative invited her readers to make comparisons to classical antiquity or mythology, our concerns were historical and theoretical (what if the path was through here and not there? Were these the kinds of ferns Oakes Smith describes in her narrative? Oh look! Pitcher plants—just like she wrote about!). To this point (and in following EOS to this point in her account), I been working on ideas, which means I had no idea what these women had done.

On this trip in 2022, I would find out what it was like to do.

In order to follow the old Keep Path completely off the established trails, I needed more permissions than ever, and it was required by the park that I take with me not one but two guides (one to stay with a person who had been injured, and the other to go for help). Fittingly, mine were two women, Jesika Lucarelli and Tallie Martin, from Great Mountain Guide Service, both closer to Mosman’s age in 1849 than Oakes Smith’s. They informed me that we needed to mark our trail with neon plastic ties in ways that ensured we would know our way out again. They forced me to carry more food than this non-climber can imagine for a day-long hike (and we ate pretty much all of it). The weather had been sweltering until the day appointed for our hike up the Brook, but that morning (as if a historical switch had been thrown) the rain came down steadily, with a temperature ranging in the high fifties—making our weather much more like that in which Oakes Smith and Mosman had made this journey. Like them, we were glad the rain drove away the mosquitoes.

Packing a Go Pro, my smartphone and some changes of socks and extra layers in my backpack, along with a couple thousand calories of food, I waded into the cold stream, now on the rise, and plunged ahead. In less than five minutes we were all soaked through, wherever we weren’t covered in gortex of some kind, and those areas wouldn’t be dry for long. For some hours, adrenaline kept us going at a steady pace, picking our way over boulders in the stream at times, losing our footing on slippery stones and plunging up to the hip in deeper pools, and scrambling on the bank whenever a moose trail had cleared some of the thick foliage. Tallie carried a Garmin to determine our position on a crude map of the terrain, but when the stream began to divide into forks in the direction of the mountain, it was difficult, without having done the hike previously, to know the right fork to pursue. Somewhere, Stan Tag was shaking his head.

Of course, this was our undoing. Having traveled what we believed to be the right distance before heading north to the avalanche, we took one of the stream’s forks and began to climb. By this time, every pause for water or food brought on a chill, so we kept moving, and for a while it seemed we would soon find the opening made by the avalanche. But the stream we were following began turning in what was clearly the wrong direction finally disappearing into completely impassable underbrush. When we could push no farther into the thicket, Tallie’s Garmin placed us only a few hundred yards from an established trail well short of Avalanche Field. Dispirited, wet through, and now concerned with signs of any onset of hypothermia, we turned around for a three hour descent downstream.

The only comfort, I suppose, was knowing Thoreau didn’t make it either.

We can read about Elizabeth Oakes Smith and Nancy Mosman and the other women (and men) who, without any of our sartorial or directional technology, managed to reach Katahdin’s summit the way Marcus Keep had designed. But I would argue that we can’t know that much about these predecessors until we make the experiment ourselves. Even allowing that the men on their trip did the carrying, the women who climbed Katahdin in the early years possessed a physical endurance and determination our reading and writing can hardly suggest. If we don’t see much in the historical record to let us know who Nancy Mosman was, this was a way to get to know her—and Oakes Smith—just a bit better.

On my way back to Chicago, I stopped in Bangor to see if the local historical society knew of Mosman, whose husband, as Geller tells us, ran a hardware and dry goods store at the time. No luck, though curator Michael Bishop did let me know about the first licensed outdoor guide in the State of Maine, Flyrod Crosby. At the public library, Betsy Paradise helped me find a directory that verified Mosman’s residence there in the year 1849, and reminded me (with Geller) that Mosman was buried in Reading, Massachusetts. Later, searching her family on Ancestry.com, my graduate assistant Sylwia Jurkowski located some of her living descendants in Houston, Texas, and I left a note for them on that site, knowing many users do not visit often. Tracking down their address in Houston, I put my MS from the chapter from The Selected Writings on the Katahdin climb in the mail and hoped I might get some response.

Months later, I received a return message on Ancestry.com. The family had received my envelope, but I’d used soluable ink on my return address, so they could only respond this way. Miraculously, in fact they did have an image of their great great great (great?) grandmother Nancy, and one of her father, Nathaniel Crockett, both oil paintings executed around the time of the women’s adventure or a bit afterwards. Finally, my contact, Karen Dean, extracted the paintings from a storage facility and sent me a quick image from her smartphone.

Only having attempted to match her feat in 1849 do i feel I can read the smile on her face.

Section of an oil painting of Nancy Mosman (as yet unidentified artist), courtesy of the Dean Family.

POSTSCRIPT, Summer 2023:

Through the generosity of the Dean family, a $1500 contribution from the EOS Society for shipping, and the work and expertise of the Maine Historical Society, the original portraits of Nancy Crockett Mosman and her father are preserved as part of the Brown Library’s collection in Portland, ME. Many thanks to Karen Dean and Tiffany Link for their work in the preservation of these material remains of women’s history.

Oakes Smith, Thoreau and the Shadow of Katahdin

Oakes Smith began her lecture career in June of 1851 at Hope Chapel, where she spoke on “Dress: Its Social and Aesthetic Relations.”

Only six months later, she had written four new lectures and delivered them in Brooklyn, in Worcester MA, in Portland ME, and on Nantucket Island. Through Wendell Phillips, or else by writing directly to the Lyceum at Concord, she booked a lecture among the Transcendentalists for December 31. Her subject was “Womanhood.”

Oakes Smith began her lecture career in June of 1851 at Hope Chapel, where she spoke on “Dress: Its Social and Aesthetic Relations.”

Only six months later, she had written four new lectures and delivered them in Brooklyn, in Worcester MA, in Portland ME, and on Nantucket Island. Through Wendell Phillips, or else by writing directly to the Lyceum at Concord, she booked a lecture among the Transcendentalists for December 31. Her subject was “Womanhood.”

As Secretary of the Concord Lyceum, Henry David Thoreau was the one who wrote out her contract, which would pay her $15 for the engagement, according to records—somewhat less than other figures had been paid that year. Thoreau also served as host of sorts, escorting her that evening, and even being so gallant as to carry her lecture in his pocket for her as they walked and talked.

The experience was disappointing, according to Thoreau. For some reason, he found Oakes Smith too much of a “lady”—for all her talk of anything new. She wore cologne, and he smelled it on himself back at the house (how emasculating, Dave!), but much worse, he felt himself unable to “deliver” the truth to her (as if it was his to deliver)—rather allowing his sense of gallantry to replace the “higher law” of frankness. Sounds like someone disappointed with his own inability to reject the “forms” of social grace, but you decide:

This night I heard Mrs. S----lecture on womanhood. The most important fact about the lecture was that a woman said it, and in that respect it was suggestive. Went to see her afterward, but the interview added nothing to the previous impression, rather subtracted. She was a woman in the too common sense after all. You had to fire small charges: I did not have a finger in once, for fear of blowing away all her works and so ending the game. You had to substitute courtesy for sense and argument. It requires nothing less than a chivalric feeling to sustain a conversation with a lady. I carried her lecture in my pocket wrapped in her handkerchief; my pocket exhales cologne to this moment. The championess of woman’s rights still asks you to be a ladies man.

Did Oakes Smith “ask” Thoreau to be a ladies man? One wonders in what language she did that.

But things go much deeper than this.

What seems much more important about this meeting—and one cannot know that the subject wasn’t broached—only that neither party recorded it—is that here together were two, even at that date, of the very few white people who had attempted to climb Mt. Kahtadin, the highest peak in one of the remotest wilds of the State of Maine. Comparing their accounts of the journey—both running into foul weather—Oakes Smith seems to have made it a bit farther toward the summit, and that climbing in a dress! One wonders, indeed, if the resentment one hears behind Thoreau’s journal record has something to do with this comparison, since Oakes Smith was well known for the occasional sarcastic barb. We’ll never know.

What we do know is that when Oakes Smith wrote to the Concord Lyceum Secretary again in 1855 offering her lecture on Margaret Fuller, Fuller’s Transcendentalist brother declined, indicating that the Lyceum had over-committed itself for the season.

THS

Oakes Smith's lost (fourth) "Indian" Novel

At a union service during “Old Home Week,” in an address entitled “Castine, Sixty Years Ago,” George Adams predicted a growing interest in the history of this tiny town on the Maine coast:

As time rolls on, more and more poetic interest will gather around the names of D’Aulnay, and La Tour, and Friar Leo, and Baron Castin; other pens will be enlisted to add to what has already been so well done, in rescuing from oblivion the incidents and legends of the past, and in immortalizing in fiction and romance the events of our early history…

At a union service during “Old Home Week,” in an address entitled “Castine, Sixty Years Ago,” George Adams predicted a growing interest in the history of this tiny town on the Maine coast:

As time rolls on, more and more poetic interest will gather around the names of D’Aulnay, and La Tour, and Friar Leo, and Baron Castin; other pens will be enlisted to add to what has already been so well done, in rescuing from oblivion the incidents and legends of the past, and in immortalizing in fiction and romance the events of our early history. The steady growth of antiquarian interest and research in this country is sure to reach after, and draw out to the light, and embellish in ever richer illustration and detail, the ample materials for study which belong to the events that have transpired here.

Which of us (outside of Maine) has heard of Castine, or the Bagaduce Peninsula? One doesn’t have to be a Cape Codder or even a New Englander to have read about the Pilgrims and Plymouth Colony of the 1620s, but here is a town founded (at least in its colonial guise) some years earlier than Plymouth, in the first decade of the 17th century, with a diverse history involving Dutch, British, French and Native American conflict, dispossession, repossession, and at times even cohabitation whose “rich history” has hardly enjoyed the attention predicted so confidently by its historians in 1900. In fact, the place seems to have fallen out of our records completely, its cultural life flickering feebly on by the light of locals in the Castine Historical Society newsletter.

I don’t know how I would have heard of it without finally running across a 300 page MS some years ago in the Oakes Smith papers at the University of Virginia—a document I’d overlooked on several trips there over the past two decades. Though Elizabeth Oakes Smith lived some hours west of Castine and Mount Desert during her early life, in her later career she drafted a novel (untitled in the MS we have) featuring the Baron de Castine set in the 1680s, at a time when French, British, and Native American cultures lived together in the place. I’m only 125 MSS pages into a transcription of the novel, but several features of the work will be of interest to EOS scholars:

1) Along with the unpublished novel MS entitled “The Queen of Tramps,” this untitled work is Oakes Smith’s latest novel-length work, adding a fourth “Indian novel” to her canon treating Native American/European conflict (The Western Captive, 1842; The Sagamore of Saco, 1868; The Bald Eagle, 1849/1868). Internal references to “fashionable” people summering in the area “today” date the manuscript (so far) to the last quarter of the 19th century (the first large hotel on Mount Desert was built only in 1883).

2) While all three of Oakes Smith’s published Indian novels work through difficult political issues for women and Native Americans, they do so in ways marketable for the popular press; as we now know, The Western Captive was advertised for sale in the “Books for the People” series as a cheap celebration of the exploits of the future or recently deceased President Harrison, and the latter two were written on the formula of Beadle’s dime novels series. This manuscript, by contrast (at least in its first 3rd) eschews action for description: long digressions on features of the landscape seem to bear their own interest and focus never, or only loosely, integrated into the novel’s action. Women characters—both Indian and Puritan—clearly reprise Oakes Smith’s feminist critique of the place of women in marriage—and in ways it’s hard to deny, express an older woman writer’s backward look at the effect of patriarchal pressures on her earlier life.

I don’t know how the novel ends; in fact even at this point (124 pages of some 300) I’m not sure what the conflict is! It is, however, “historically” based, and researching the time and place, we find the Baron de Castine led a war-party alongside Native American tribes against the English settlement of Pemaquid in 1689.

Of course once one happens upon such a document, allusions to its referential landscape and characters start appearing everywhere. Strange to find Oakes Smith’s Maine brother Longfellow writing a poem about the Baron in the late 1870s, narrating next to nothing about his life in the colonies. Longfellow’s Castine scandalizes his father by marrying an Indian bride, whom he brings along on his return home to France, and makes “good” on the marriage, previously consecrated only by Native American ritual, by remarrying in the church, and hence “coming home” to his own. That Oakes Smith begins her novel with a reference to this “proper” marriage, but shows it performed by a French Priest at Castine’s castle in the (then) French colony, makes one wonder if Oakes Smith was beginning to “embellish” the record in the way George Adams had predicted by supplying the story—or legend—of Castine’s “American” life in the early 1880s.

More soon.

More Archive Adventures: More Context for “The Black Fortune-Teller”

Elizabeth Oakes Smith is my longest-running research interest and my most recent foray into her work is a study of her first piece of fiction, a short story titled “The Black Fortune-Teller” (1831). I first encountered this story back in 2013 when I was working my way through the Maine Historical Society’s archives of 1820-30s newspapers…

Elizabeth Oakes Smith is my longest-running research interest and my most recent foray into her work is a study of her first piece of fiction, a short story titled “The Black Fortune-Teller” (1831). I first encountered this story back in 2013 when I was working my way through the Maine Historical Society’s archives of 1820-30s newspapers. I remember being puzzled by its departure from her usual style but brushed it aside at the time as a project for another day. I would not return to it in earnest until earlier this year, when I was asked to join a panel Tim Scherman organized for the ALA conference last spring.

“Fortune-Teller” does not lose its intrigue upon closer scrutiny. Although numbering little more than a thousand words, it packs a punch. To briefly summarize, the titular fortune teller is an escaped slave named Cleopatra who makes her living in the north who is visited one night by a mysterious woman in a cloak. In a not-unexpected twist, we discover that the woman is Cleopatra’s old mistress, now fallen upon hard times. Ultimately, Oakes Smith capitulates to popular narratives of the time and closes her tale with Cleopatra returning to a life of service, but not without Cleopatra’s insistence that she be paid for her labor.

There are several things I find fascinating about this story: a black female subject, said subject’s demand to be paid for her labor, and the inclusion of a flashback to Cleopatra’s kidnapping by slavers that is blatantly sympathetic to the captured rather than their white captors. The common thread weaving through these points of interest is the opportunity to analyze not just Oakes Smith’s attitudes towards race, but those of 19th century Portland as well.

As part of my efforts to contextualize “Fortune-Teller,” I needed to understand its immediate context in the newspapers of the time. I submitted a request to the Maine Historical Society (MHS) for any newspaper articles on the subject of abolition for the period of 1829-1831. The abolition movement was still very much a fringe movement at this point in time, but It was my hope that their findings would shed some light on what the people of Portland were publishing. Their findings did not arrive in time for the conference, but they were worth the wait.

The MHS archive did not contain any newspapers dating earlier than March 31, 1831, but they were able to find three articles from that year on the subject of black Americans: “African Ideals of Beauty,” “Ethiopian Variety,” and “A Noble Action.” As their titles suggest, they represent different genres, which I expected, but I was surprised to find that their contents were also in sharp contrast.

“African Ideals of Beauty” is a throwaway snippet maybe an inch high about how white skin and upturned noses are considered unattractive to African women, and seems to have been inserted purely to use up empty space. “Ethiopian Variety,” on the other hand, is the lengthiest of the three and sprawls over several columns. Clearly written by a person under the influence of phrenology, it implies that Africans are a different species altogether and at one point references how a monkey can be mistaken for an Inuit. The tone of the piece is vaguely amused and certainly dismissive, and seems to exist to catalogue perceived differences between African people and Europeans in order to reinforce a sense of Euro-supremacy. In short, it was what I was expecting to find.

Occupying the other end of the spectrum is a sentimental story titled “A Noble Action,” which proves to be a likely source of inspiration for “Fortune-Teller.” It describes a wealthy woman who rewards her slave’s years of labor by emancipating him and gifting him a large sum of money, which he uses to start a new life. Later, when she loses her fortune and place in high society, he insists that she live with him and his family, where she is treated with “respect” and waited on hand and foot. American literary history of full of tales of loyal slaves and kind masters, a narrative that runs directly counter to the actual lived horrors of the time. Nowhere in this story is there any hint of the peculiar institution’s inhumanity. Instead, it paints a sappy picture of the virtue of servility and reinforces the myth that slavery is a natural state of affairs. Its message is clear: emancipation is a nice gesture, but it cannot change the fact that there are those who were born to serve.

On the surface, “Fortune-Teller” seems to follow the same logic. Cleopatra was also a self-sufficient person of color in antebellum America who decides to return to a life of service with her old mistress after years of freedom. However, there are some key differences. Firstly, Cleopatra was not emancipated; she escaped from slavery on her own strength. Second, she does not provide her labor pro bono but demands what every working person deserves: payment for services rendered. The third and most compelling difference is the sympathies of its author. Rather than glide over how people are made into slaves or presenting it as an eternal, natural state of affairs, Oakes Smith describes how Cleopatra and her sister were stolen from their home and forcibly brought to America. There is nothing natural about this process, and Cleopatra’s reluctance to leave her independence shows that no person in their right mind would brush aside their freedom to return to service, regardless of whatever kindnesses their old master showed.

These widely diverging texts, published over the course of a year in Portland’s newspapers, serve as evidence that there are no straightforward answers or simple binaries in the history of race and America. It is easy to see white Americans of the 19th century as clearly on the side of abolition or slavery, to ascribe to them the clear thinking that hindsight provides, but those positions were not yet defined as we know them today. It is important to create distance between what we know today and the history of our ideals, to preserve complexity rather than washing it away. This short story was published in the year of Nat Turner’s rebellion, a time of tremendous tension and great anger on the part of whites against black Americans, and yet Oakes Smith gives her heroine the name of a famous queen and showed her readers that it is a struggle to choose between freedom and service. In “Fortune-Teller,” unlike its cousin in the pages of the Courier, “Ethiopian Variety,” there is no natural order tied to the color of one’s skin.

Abigail Harris-Culver

Early 19th century "Emoticons?"

I recently presented a paper at the recently renovated Yarmouth History Center at the invitation of its (then) Interim Director Amy Aldredge. I had come, I told the audience, to ask their help, for my thesis was that too much of what we know about her--really the whole orientation of our understanding of Oakes Smith's work--is probably weighted much too far toward her late reflections on her career available in her autobiography…

I recently presented a paper at the recently renovated Yarmouth History Center at the invitation of its (then) Interim Director Amy Aldredge. I had come, I told the audience, to ask their help, for my thesis was that too much of what we know about her--really the whole orientation of our understanding of Oakes Smith's work--is probably weighted much too far toward her late reflections on her career available in her autobiography. We need to locate material evidence to fill in the details of Oakes Smith's early life if, for nothing else, to counterbalance the autobiography's tone, which is at best wistful, at worst cloyingly self-pitying. Who better to help us with this task but folks who live in the place, and who have taken an interest in its history?

With the help of two graduate students, Rebecca Wiltberger and Abigail Harris, I had begun to do this work the previous summer, trying to get a sense of Oakes Smith's earliest apprenticeship as a writer and editor in the 1820s and 30s, when she was first married to Seba Smith. During a three-day stint at the Maine Historical Society Library in Portland, Abigail chased down the larger part of her earliest writings in Seba's Courier and Family Reader, while Rebecca worked on contextualizing what Portlandians like Oakes Smith were reading in newspapers about Native American affairs (later in her years in Portland, she'd be writing The Western Captive, or at least thinking about it).

Only in this recent context did I realize I'd actually begun to fill out Oakes Smith's early life some years ago in the archives at the University of Virginia, even if the earliest letters document only about a month's time. These few weeks were the first Oakes Smith and her husband had ever been separated for more than a day, when Seba Smith checked into a Boston hotel to see his first volume of Jack Downing letters through the press. Of course, since "marriage" as a patriarchal institution would be the target of an enormous amount of Oakes Smith's writing, these letters, which tell us quite a bit about her relationship with her own husband, seem especially important.

So I spent some time, in my paper, detailing these letters, demonstrating how the dismissive tone regarding her marriage and her husband that characterize her later reminiscence in the autobiography does not square at all with this private correspondence. And lest we see the letters as tinged by the "honeymoon" phase of the relationship, we should acknowledge that they were written some months after the couple's tenth anniversary, in late October and early November 1833.

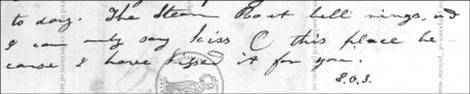

The letters are amazingly...well, the only word that suffices might be "fond"--not just comfortable, but devoted, loving, and sort of silly. And that goes for both letter writers. To get to my title, I'll only include here my favorite example of this tone, with which Oakes Smith closes her letter of November 11, 1833. Unable to send Seba a kiss, she puts her lips to paper, draws a circle at the spot (this is, indeed, better than an emoticon) and asks him to kiss the same.

We can't avoid at least thinking it, right?

(Aww...)

"The Steam boat bell rings, and I can only say kiss this place because I have kissed it for you"

On a recent visit to the archive...

This past October I dropped everything and took another trip to Charlottesville, where five feet of Elizabeth Oakes Smith's MSS are held in the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library. My first priority was to have a closer look at the early letters between Oakes Smith and her husband, written between 1833 and 1837, which will form a section of my projected edition of her writings…

This past October I dropped everything and took another trip to Charlottesville, where five feet of Elizabeth Oakes Smith's MSS are held in the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library. My first priority was to have a closer look at the early letters between Oakes Smith and her husband, written between 1833 and 1837, which will form a section of my projected edition of her writings. This was clean-up: a long stare at words I couldn't make out on xerox copies, a look at envelopes to glean further evidence of the context of their correspondence. It's a fascinating chapter in Oakes Smith's life, and further, as I argued in a paper delivered at the Yarmouth History Center last June (a 75- minute marathon, much to my host's surprise), this is a series of documents that might cause us to change the way we view the assumed relationship between much of her fiction and her life. But more on that another time.

The "news" on this trip came after I completed my examination of these few dozen letters. It was exam time on campus, so my extended weekend trip would only mean three days in the library, and not four, but I had some time on this trip to explore the collection's holdings in ways I had not before. Two of my previous three trips were made before the days of the iPad and the smart phone, either of which provides photographic equipment that reduces what used to be a painstakingly slow process of copying (I'd tried pencil, laptop, and dictation in the 90s) to a much more efficient physical review of documents, intellectual determination of their research value, and instant, manipulable digital reproduction with a click every ten or twelve seconds. In this mode, I had time to deal with works I had in the past simply passed up as too large to work with given my limited time in the library: two unpublished novels in MS, manuscript copies of three EOS plays, diaries and journals by EOS from the 1850s and 60s, and perhaps most strange, the hand-illustrated journal of her youngest son Edward, who in his mid-twenties had dreams of becoming an art critic.

To lower expectations for any analysis here (and perhaps pique interest in a visit for anyone in the Southeast), I only had time to briefly skim all of these large documents as I hastily reproduced them digitally for later study, but the basics are these:

1. The largest document, a novel called The Queen of Tramps, is mistitled in the collection's on-line index (Trumps instead of Tramps), and the difference is significant. When the Oakes Smith family came together for about a year to publish The Great Republic Monthly in 1859 (succeeding the parents' co-editorship of Emerson's Magazine and Putnam's Monthly), the magazine included a series on the working classes of New York City ("The Rag Pickers of New York," "The Firemen of New York," etc.), and in her novel The Newsboy (1854) Oakes Smith had taken some pains to detail the conditions of the working poor in somewhat more detail than we find in, say, Southworth's The Hidden Hand (1857). The unpublished manuscript of The Queen of Tramps (which I had to carefully remove from some rather tightly knotted cording--so I don't think a lot of people have ever seen these pages!) runs several hundred manuscript pages, penned in a hand that seems to date from this middle period, and from what I skimmed, it seems to involve a woman of some means moving into the slums of New York.

2) The second unpublished novel in manuscript is missing a title page. Again it runs some hundreds of MS pages--taking up historical and regional settings Oakes Smith had already explored in published writing: colonial life in what is now the state of Maine, and the relations between Native Americans and the new colonists.

3) To this point the only play I've read by Oakes Smith is Old New York (1853), although I've also seen mention of one entitled The Roman Tribute. Here, in the EOS collection, I discovered the bound manuscript (in leather, with hand-lettering on the spine) of a play entitled Destiny, along with a clippings of a novella of the same title in another folder. Here, too, is The Roman Tribute, in a fascinating form: the players' personal editions, copied in meticulously bound and organized parts. Notes in the margins are too detailed for this not to have been used in performance, or in preparation for a performance.

4) Edward's journal made the most delightful reading. Punctuated with drawings and doodles that reveal a practiced (if not formally trained) artist, the section I read in detail features Edward's professional struggles. If he can't make a go of art criticism, he decides (in something of a sarcastic tone) to try writing a "penny dreadful" of sorts to sell. In the end, what may have begun as a lark gets written and sent around to publishers; Edward is even kind enough to posterity to copy the crude horror story into his journal for us.

Folks interested in these documents should contact me and/or UVa's Special Collections department for more details.

THS