Early 19th century "Emoticons?"

Jan 2015—I recently presented a paper at the recently renovated Yarmouth History Center at the invitation of its (then) Interim Director Amy Aldredge. I had come, I told the audience, to ask their help, for my thesis was that too much of what we know about her--really the whole orientation of our understanding of Oakes Smith's work--is probably weighted much too far toward her late reflections on her career available in her autobiography. We need to locate material evidence to fill in the details of Oakes Smith's early life if, for nothing else, to counterbalance the autobiography's tone, which is at best wistful, at worst cloyingly self-pitying. Who better to help us with this task but folks who live in the place, and who have taken an interest in its history?

With the help of two graduate students, Rebecca Wiltberger and Abigail Harris, I had begun to do this work the previous summer, trying to get a sense of Oakes Smith's earliest apprenticeship as a writer and editor in the 1820s and 30s, when she was first married to Seba Smith. During a three-day stint at the Maine Historical Society Library in Portland, Abigail chased down the larger part of her earliest writings in Seba's Courier and Family Reader, while Rebecca worked on contextualizing what Portlandians like Oakes Smith were reading in newspapers about Native American affairs (later in her years in Portland, she'd be writing The Western Captive, or at least thinking about it).

Only in this recent context did I realize I'd actually begun to fill out Oakes Smith's early life some years ago in the archives at the University of Virginia, even if the earliest letters document only about a month's time. These few weeks were the first Oakes Smith and her husband had ever been separated for more than a day, when Seba Smith checked into a Boston hotel to see his first volume of Jack Downing letters through the press. Of course, since "marriage" as a patriarchal institution would be the target of an enormous amount of Oakes Smith's writing, these letters, which tell us quite a bit about her relationship with her own husband, seem especially important.

So I spent some time, in my paper, detailing these letters, demonstrating how the dismissive tone regarding her marriage and her husband that characterize her later reminiscence in the autobiography does not square at all with this private correspondence. And lest we see the letters as tinged by the "honeymoon" phase of the relationship, we should acknowledge that they were written some months after the couple's tenth anniversary, in late October and early November 1833.

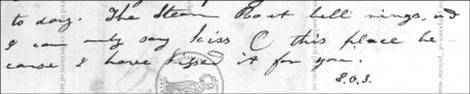

The letters are amazingly...well, the only word that suffices might be "fond"--not just comfortable, but devoted, loving, and sort of silly. And that goes for both letter writers. To get to my title, I'll only include here my favorite example of this tone, with which Oakes Smith closes her letter of November 11, 1833. Unable to send Seba a kiss, she puts her lips to paper, draws a circle at the spot (this is, indeed, better than an emoticon) and asks him to kiss the same.

We can't avoid at least thinking it, right?

(Aww...)

POSTSCRIPT: all these letters—and some from their separation in 1837 as well, are now available to readers, edited and annotated, in Elizabeth Oakes Smith: Selected Writings, Volume I—Emergence and Fame (Macon: Mercer UP, 2023).

"The Steam boat bell rings, and I can only say kiss this place because I have kissed it for you"